Jemima, a 6 year old female Red Tailed Hawk (Buteo jamaicensis) presented last month as an emergency with haemorrhage from a cloacal prolapse.

With the intestine, ureters from the kidneys and oviduct (egg tube) all meeting at the cloaca any of the above tissues can be involved in such a prolapse, as well as a variety of cloacal lumps and bumps (see previous website story on cloacal papillomatosis).

This is a genuine emergency as with the prolapsed tissues turned inside out, obstructing the faecal and urine output, the bird can very quickly go into irreversible kidney failure in addition to the risk from significant haemorrhage.

Time is of also of the essence, as with the blood supply seriously compromised in such situations, the fragile exposed tissues very quickly start to die off.

Causes of such prolapses include chronic straining as a result of egg binding, intestinal/cloacal inflammation, foreign bodies or masses, faecal/urate impaction, oviduct infection, bacterial/viral/parasitic enteritis or tumours.

From the appearance of the tissue and timing outside of the breeding season we deduced we were dealing with an intestinal prolapse. A simple manual replacement of the tissue was not an option as the tissue was turned inside out and with the end already necrotic; even if it could be replaced, tissue death would inevitably lead to rupture, leakage of intestinal contents and resulting peritonitis (massive infection of the body cavity).

Given the above, the owner was given a poor prognosis with surgical intervention Jemima’s only hope.

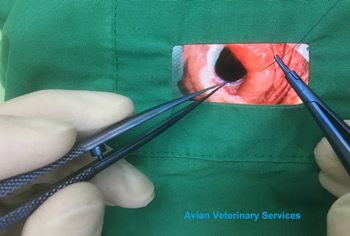

Before embarking on surgery, we assessed the internal organs with the endoscope via a ‘keyhole’ between the last two ribs to ensure the obstruction had not already caused permanent intestinal damage. Apart from the guts being massively dilated with contents starting to back up, due to the vigilance and swift action of the owner, the tissues still looked viable and as such we went ahead with exploratory surgery.

Radiosurgery (an electronic scalpel that uses radio waves to cut and seal blood vessels) was used to very carefully enter the body cavity and avoid cutting into the dilated gut loops.

There was no evidence of tumours or a foreign body, but for some reason the small intestine had telescoped into itself (intussuscepted) and passed all the way through the large intestine and vent and with its blood supply now compressed, was starting to die off.

Approximately 6 inches of the ‘telescoped’ intestine was carefully manipulated back into itself and straightened out revealing a section of about 2 inches that was already beyond repair and would have to be removed.

With the small scale and delicate nature of the avian intestine (approximately 4-5 mm diameter in this case) such surgery is virtually impossible without microsurgery instrumentation, designed to be operated with the fingertips, and the magnification and focal LED illumination of our 3.5x surgical loupes.

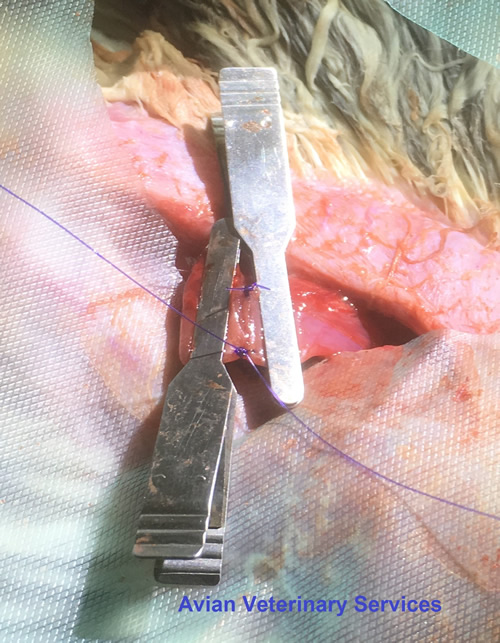

The damaged section of intestine was isolated using ‘atraumatic’ clamps that prevent gut leakage without causing damage to the delicate tissue, (these clamps are actually borrowed from human surgery where they are used to repair blood vessels), its blood supply managed with the radiosurgery and about 2 inches of damaged gut removed.

The cut ends were then reattached via an ‘end to end anastomosis’ using fine ophthalmic suture which in terms of scale and texture felt like we were stitching two halves of a worm back together!

The clamps were removed and once we were happy there was no leakage the section replaced into the body cavity and wound closed in 2 layers.

The following morning, we had never been so excited to see a bird poo, confirming her guts were now functional again!

Jemima was hospitalized for a few days to ensure she was comfortable, able to feed and maintain weight and there were no complications from her surgery.

Once home she continued to improve with owner struggling to keep her ‘rested’ as she was now feeling so much better and wanting to fly.

Her check-up the following week demonstrated all was good at the surgical site and so she was allowed back into her aviary for a further 2 weeks of restricted exercise.

Faecal samples were clear of parasites/infection, so no real cause for this prolapse/intussusception could be deduced at this point although of four such cases I have seen in 20 years three of them have been Red Tails so possibly a breed susceptibility exists.

We are very pleased to report that over a month down the line Jemima is finally back to full fitness and flying duties!

AVS would like to thank Dr Larry Nemetz, The Bird Clinic, California for his avian surgical training, continued support and advice on such cases.